What’s In A Name? A Book Baring Another Author’s Name Would Still Be A Treat

Last year, amidst all the chaos caused by coronavirus, something altogether more inspiring happened. To celebrate twenty-five years of the ‘Women’s Prize for Fiction’ twenty-five novels originally published under male pseudonyms were republished with the authors’ actual names. Although the ‘Reclaim Her Name’ series was criticised for its “sloppy execution”; the idea behind it was an interesting one.

There are many reasons authors choose to write under different names. There may already be someone with your name at your local bookshop, and you need to differentiate yourself from them. If your initials and surname don’t work, you might change your whole name entirely. For others, there may be something in their work that needs to remain anonymous because it draws on autobiographical elements. Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar was originally published under the name ‘Victoria Lucas’ for just such a reason. Maybe the author decides to write books in a completely different genre, or wants to write for children when they’re known for strong themes in their adult books. There are numerous reasons why writers make the decision they do now, but for a long time women change their names because they didn’t have any other choice.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth century a woman supporting herself as an author was viewed in the same way as a prostitute. Writing was a perfectly respectable profession for a man, but a woman should be at home busying herself with more domestic duties. So women released books under male pseudonyms. Obviously times and attitudes have changed, but before they did, women choosing to forgo male monikers had two choices: leave their name off the work entirely or publish slightly less anonymously, with the admission that their book was written ‘ by a Lady’. Even Jane Austen, one of the country’s most beloved authors, saw her books published in such a way. Her second book, Pride and Prejudice, was upgraded to ‘by the author of Sense and Sensibility’ but her name didn’t appear on any of her works until after her death.

We’ve ‘thankfully’ come a long way since then… so I can’t help but wonder: why are female authors still writing under male pseudonyms?

When the book City of Dark Magic was revealed to be the work of two female authors – Meg Howrey and Christina Lynch – they said they chose a male pseudonym because they wanted “to appeal to both genders”. That’s an interesting way of saying: ‘they didn’t want to put the boys off’ — a really depressing thought for a book released in 2012. The weirdest person to find on the list is J. K. Rowling. Her wanting to carve a separate adult space for her writing makes total sense… but she’d already released The Casual Vacancy under her own name. And there are plenty of successful women crime writers. Agatha Christie anyone? Rowling said she chose a male name because she “wanted to take [her] writing persona as far away as possible from [her]”. The choice is hers alone of course, but it still seems strange that a writer so frequently embroiled in heated exchanges around gender would choose to write as ‘Robert Galbraith’.

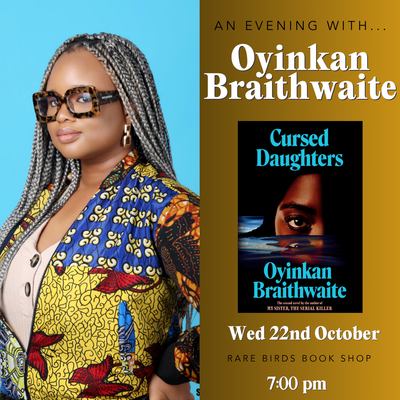

The beauty of George Eliot’s Middlemarch isn’t changed by writing: ‘Mary Ann Evans’ on the cover; just as Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre would remain as brilliant read if Currer Bell was credited. As poorly received as the ‘Reclaim Her Name’ series turned out to be, it at least brought some well-deserved attention to the work of a whole flock of brilliant rare birds.